E-commerce giant close to inking lease with Mack-Cali Realty’s Harborside 1

Tri-State /November 02, 2021 06:30 PMTRD Staff

Jeff Bezos & 50 Hudson Street in Jersey City (loopnet.com, Getty Images)

Amazon’s expansion in the tri-state area continues as the e-commerce giant reportedly eyes space in Jersey City.

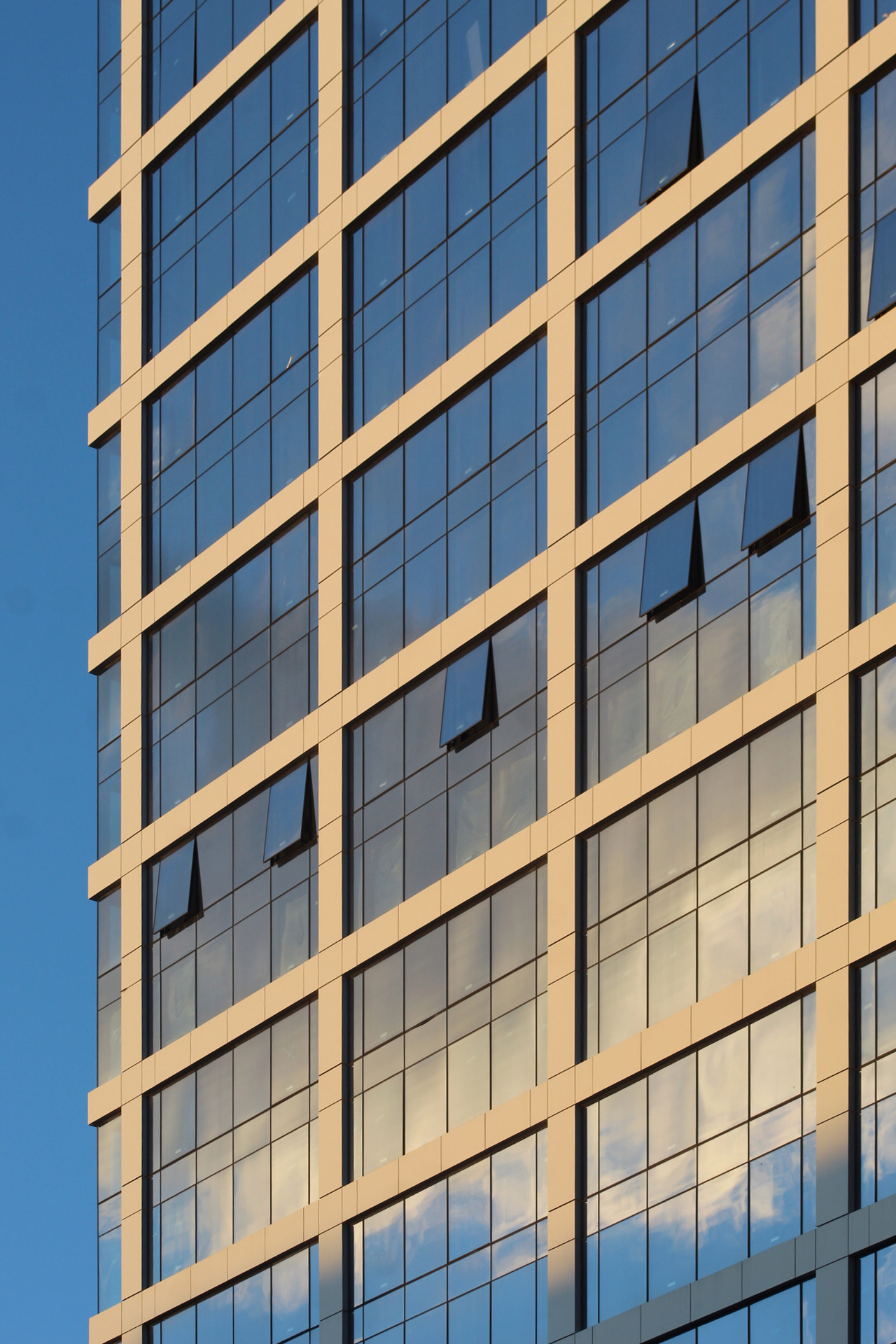

The company is close to a deal to lease 400,000 square feet at Mack-Cali Realty’s Harborside 1 in Jersey City, Bloomberg reports, citing people familiar with the potential deal. Tax breaks are available for the waterfront property at 150 Hudson Street, the developer’s website reveals.ADVERTISING

Harborside 1 is an eight-story, 400,000-square-foot building according to Mack-Cali’s website.

The company this spring completed more than $100 million in renovations on its Harborside campus, which spans 4.3 million square feet. The improvements at Harborside 1 include a new facade, new lobby and terrace views of Manhattan and the Hudson River.

The REIT was hoping the renovated spaces would attract media and creative tenants, Ed Guiltinan, Mack-Cali’s senior vice president of leasing, told the New York Post in May.

Jersey City was a contender in the competition for Amazon’s HQ2, offering up to $5 billion in economic incentives to land the corporate campus. Ultimately, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos chose to split HQ2 between Long Island City and Arlington, Virginia.

Things didn’t go so well for the company’s development in Queens. Grassroots organizations bemoaned the $3 billion in city and tax incentives that the company was poised to receive, not to mention the helipad that was to be part of the campus. Activists even objected to the high-paying jobs, saying the new employees would drive up housing prices.ADVERTISEMENT

On Valentine’s Day in 2019, Amazon abandoned its plans at the site.

However, Amazon’s failure in Queens hasn’t soured the company on the New York metro area. But it has focused it search for office space on Manhattan rather than the outer boroughs.

In December 2019, the tech giant signed a 335,000-square-foot lease with SL Green Realty for an office near Hudson Yards. The lease at 410 Tenth Avenue did not involve any tax breaks.

In March 2020, Amazon doubled down on New York City, buying the Lord & Taylor building from WeWork for $1.15 billion. The purchase price on the 660,000-square foot building at 424 Fifth Avenue worked out to about $2,000 per square foot.

[Bloomberg] — Holden Walter-Warne

601 West 29th Street. Photo by Michael Young

601 West 29th Street. Photo by Michael Young